Wrecked & righted words and photos by Merl Falkner

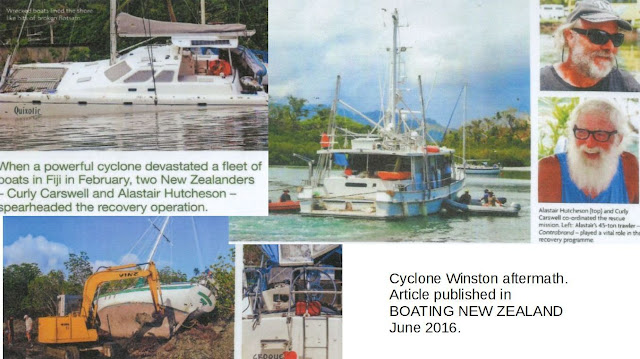

When a powerful cyclone devastated a fleet of boats in Fiji in February [2016?], two New Zealanders - Curly Carswell and Alastair Hutcheson - spearheaded the recovery operation.

As Tropical Cyclone Winston steamrolled toward Fiji, the fleet at Savusavu went on high alert. My husband, Jim, and I removed sails, canvas and other windage from our Tartan 41, Hotspur. Our 16-year-old daughter, Carolyne, tossed items from deckside down below or lashed them. Jim double-checked our mooring and covered our bowlines with used fire hose to prevent chafing.

Twenty-four hours before Winston's predicted arrival, we'd felt optimistic. But when we learned the cyclone had morphed into a Category 5 super-storm overnight, our confidence melted into a sweaty brow of doubt. Predicted gusts over 150 knots meant we might lose our boat.

Winston ambushed Savusavu - arriving almost 10 hours earlier than predicted. It bombarded the anchorage, blinding its victims in a mask of white rage. Broken lines sent manned and unmanned vessels awry, charging like attack dogs towing chewed-through chains. Some boats dragged their heavy mooring blocks, pin-balling off other boats as they hurled past, knocking them off, too.

"It was a domino effect and the root of the damage," says Curly Carswell, whose houseboat was struck 11 times by wayward vessels in the storm. Thanks to her seven-ton mooring, Curly's houseboat held. But his Downeast 38, Shangri La, was struck by two separate vessels and sent flying deep into the mangroves. "My best guess is sustained wind were 150 knots, but gusts were between 160 and 170 knots," Curly says.

And Curly would know. A delivery captain for many years, he hails from Hastings but has resided in Savusavu for over four decades. He's the Seven Seas Cruising Station contact, the Island Cruising Association 'port captain' and he runs the daily VHF radio net providing weather reports for the fleet.

With his snow-white beard and looming stature, at first glance he looks to be a bit of a boating Gandalf. Together with Alastair Hutcheson, the duo merged into 'rescue team supervisors' and were essential to the recovery of Savusavu as a tourist and cruising destination.

Alistair Hutcheson moved Contraband - his 55-foot commercial fishing trawler - from Savusavu to a nearby protected anchorage in Nadivakarua Bay before the cyclone's arrival. "I didn't feel comfortable among all the yachts and our location was susceptible to storm surge," the Tauranga native says. He took his family, including his seven-week-old baby born in Savusavu, and found shelter behind hills blocking the gustling winds.

In the storm's aftermath he tried to return to Savusavu but the sea was as muddy as a giant kava bowl. "We were confused and tired. There was zero visibility. We clipped the corner of a sandbar and the boat tipped over on its port side, " Alastair says. And it didn't thud gently. Contraband fell hard, the tremendous jolt tossing Alastair across her five-meter beam and right on top of his wife, Feriliga. Alastair injured his leg in the fall but Feriliga, though annoyed, was unharmed.

With over 20 year's experience in boatbuilding, moving boats on slipways and calculating vessel stabilities, Alastair's background came in handy. He closed the fuel balance pipes and all the valves. "The port decks lay underwater," he says, "but I knew she'd come back." And Contraband did just that. She righted with the next high tide.

It took two days to escape Nadivakarua Bay and travel the 32 kilometres back to Savusavu. Only half of Contraband's electronics functioned after her beating and Alastair didn't trust the readings of the remaining instruments. When Contraband finally limped back into Savusavu Bay, Alastair's heart sank. "There were boats on the rocks, on the reefs and in the mangroves," he recalls. "I'd never seen anything like it."

The aqua-blue water, waving palm trees and colourful vegetation before Winston's arrival were gone. Trees lay uprooted. Clusters of wrecked sailboats lined every shore. One catamaran lay listing, half-submerged and mutilated in filthy seawater. Another beached vessel was impaled on a power pole. In Winston's aftermath, 23 sailboats cluttered the shoreline like piles of discarded refuse. "The destruction was pitiful," says Alastair.

After a quick assessment, Alastair knew he could help. "I felt a responsibility to the boat owners, who have very little money," he says, knowing that salvage operators would expect as much as half of each boat's value. Some owners would have lost their boats completely."

And he knew Contraband's 44-inch propeller would have the torque needed to pull boats back into the water. Although he'd never met him, he knew of Curly's extensive background and practical abilities. Curly is well known and respected in Savusavu and when the men met they formed an alliance - and a friendship - that would change everything.

RECOVERY

They didn't waste time. "We began the recovery initiative to avoid boaters getting done over by salvage people, " Curly says. "It needed to be done quickly and had to be organized." He began by forming and shuffling cruiser volunteer teams. He also reached out to Fiji's goverment departments. "Customs, merchants, the whole townn... everyone was supportive," Curly says. Alastair, meanwhile, readied his 45-ton motor yacht and made a list of which boats would be re-floated in a succession of high tides. It didn't take long for the fleet to lick its wounds, shake off its collective stupor and take action. The cruising community merged. Men and women grabbed shovesls or used bare hands to sling mud and remove rocks from under hulls. Some grabbed pumps and rushed to purge water from leaking vessels. Teams were formed to monitor each boat. Crews patched holes. Watchful eyes looked for looters. Everyone worked together like a well-oiled machine and raced to readiness to take advantage of the tides.

"The biggest challenge," Curly says, "is that cruisers are inherently independent." Alastair agrees. "Every boat had a different set of engineering challenes and every boatowner had a different attitude toward his rescue." And there was another factor. "I believe many people suffered psychologically from the efects of the storm," Alistair says.

But boat after boat was re-floated. And locals, too, rushed to lend a hand. When the 40-foot monohull, Distant Beat, needed some extra muscle, a dumptruck pulled over, hooked up to a pulley system and helped heave. Cheers erupted when she rolled over so the team could work on the next phease of her release. "It wasn't a matter of backing the boat up, sticking on a rope and pulling a beached vessel into the water, " Alastair says. "Most of the boats needed a week's worth of serious prep beforehand."

Our boat Hotspur, survived the storm with minimal damage. My husband, Jim, joined several crews responsible for keeping water on the outside of grounded vessels and helping boat owners prep their boats before a pull. And some people needed emotional support. "There are only so many high tides, ons so many ropes and only one rescue boat," Jim says. "It was hard for people to be patient."

Even those with bitty biceps (like me) joined forces. Some spearheaded spare parts deliveries from overseas. Some offered to scribe meeting minutes and distribute them. Others ran errands or shuttled pumps, fenders, ropes and other equipment back and forth.

The rescued cruisers felt overwhelmed with appreciation. "I would have become mosquito fodder, says Andre Schwartz of his 39' Oceanis, Symbiosis. "I don't think I would have salvaged my boat myself and I'm incredibly grateful to everyone."

Mark Whitehead concurs. When his Endurance 37, Karma, was finally rescued he said, "Many cruisers selflessly gave me their time, help and support." Even though Karma still needs many repairs he says the cruisers gave him hope when he was ready to write his boat off.

Tropical Cyclone Winston knocked the wind into (and out) of us in Savusavu. But our collective ingenuity, mixed with a little spirit and grit is a classic example of just how far cruisers are willing to go to help other cruisers. Two months after Winston's assault, 18 boats of 23 are floating because of the blood, sweat and tears from volunteer cruisers.

Alastair and Curly believe it would have cost many thousands of dollars to hire a tug to do what we all did together. Both believe many owners would have given up. "I've never read of a similar situation where cruisers got together and sorted out this kind of mess," Curly says. Alastair agrees: "I just happened to have the right boat and a good background. But it wouldn't have happened without the team of helpers.